These are summaries of the talks I attended during day two of the OxfordTEFL Innovate ELT online conference on 1st and 2nd October 2021. Day one is here.

Note: when I’ve included links, sometimes they’re the ones the presenter included, sometimes they’re others which I’ve found. If you’re one of the presenters and would like me to change any of the links, please let me know!

Plenary – Writing for yourself and the rest of the teaching community – me 🙂

Here is a link to the blogpost detailing my talk.

Plenary – Not just diversity, but unity – Fiona Mauchline

If we’ve learnt anything in 2020-2021, it’s that we need people: to shape our lives, and to learn. Emerging from such isolating times, let’s reflect on how to employ not just ‘people in the room’ ELT approaches, but ‘between people in the room’ approaches. Connection: what language is for.

Fiona reminds us that while of course it is important to get more voices in the room and to focus on diversity, it is also important to consider the connections between the people in the room. She asked us:

- What two things did you most miss about life while in lockdown or under restrictions?

- What do you most miss about face2face conferences/ELT events?

- How do you feel about group communication in a Zoom room with more than 3 people?

She reminds us how important it is to get students talking as early as possible in a session or lesson to break the ice and help students to feel comfortable sharing ideas – these questions were an example of that kind of activity.

Most of the answers in the chat showed that we missed the social aspects of life. There has been a lot about changing narratives and diversity over the past year, but the most important thing Fiona has noticed has been the need for connection and unity. Cohorts who met entirely online and never had any contact face-to-face first seemed to have less effective learning. Fiona shook up her teaching, for example by including sessions where she set things up and left the lesson for a while to give the students space and to move the focus away from her.

In many classrooms, both face-to-face and online, we all look in the same direction, which our brain interprets as a non-communicative situation. We’re all separate online, in different boxes, which our brain interprets as being apart and non-communicative. Even face-to-face, it’s hard to find images of classrooms with people really looking at each other – again, the body language implies not communicating.

We need to look at physically moving learners into communicative modes, rather than just having them speak to each other. Build on the social in your classrooms. Here are some ideas to do this:

Fiona said her plenary last was a ‘call to arms’ and this year it’s a ‘call to hugs’ 🙂

Fostering Learner Autonomy in Virtual Classes – Patricia Ramos Vizoso and Urszula Staszczyk

We all want to see our students bloom and become more autonomous learners. In this talk we will look into some practical ideas that can empower them to be more active and conscious participants in their language learning process, making the whole learning experience a memorable one for both them and us.

Learner autonomy is important because it leads to more efficient and effective learning (Benson, 2011). It helps them to become lifelong learners. Learners are more invested in their learning, and therefore more motivated, because they choose what works for them. They also understand the purpose and usefulness of lessons. Class time is not sufficient – learners need more time to really learn a language.

These are possible ways of focussing on learner autonomy:

In this talk, Ula and Patricia will focus on learner-based and teacher-based approaches.

To implement learning autonomy in class, be aware that it’s a process – it needs to be done regularly, step by step. For example, start by giving them choices (Do you want to do this alone or in pairs? Who do you want to work with?) You have to be consistent and patient – results might not be immediate. The teacher is a facilitator, not the source of knowledge. Try different things, and don’t be afraid to take risks – different things will work for different groups.

We could say that there are 3 phases of learner autonomy:

- Kick-off: All learners have the potential to be autonomous, but we need to develop this potential. Teachers are there to help learners understand what that potential is and what options learners have.

- Action: This is the ‘doing’ phase.

- Reflection and Evaluation: Learners decide what worked and what didn’t.

Kick-off

Set goals: SMART objectives, a class goal contract, or unit objectives. Discuss these goals, keep track of them, and when learners lose motivation or go off track, discuss the goals again. Possible headings to help learners frame their goals:

- What is your goal?

- How do you plan to achieve this goal?

- When and how often will you do the work?

- How long will it take?

- Who will evaluate your progress? How?

Learners might not know how to create goals like this, and will probably need support. Here is an activity you could do to help them, by presenting problems and solutions which students match, and learners decide which strategies they want to try out.

Acting

Give students choices in class:

- Who will they work with? When?

- How will they do tasks? Written, oral, video…?

- What materials will they use?

- What do they want to improve?

Encourage them to think about why they make these choices, not just what the choices are.

Another idea is a choice board:

The phrases on the right are feedback Patricia got from her students, which she conducted in their first language.

Other ideas for action: encourage peer correction, create checklists with students, flip lessons, micro presentations (1-3 minutes) based on topics they’re interested in, task-based learning, project-based lessons.

You can adapt activities from coursebooks or other materials you’re using to make tasks more autonomous – you don’t have to start from scratch. Small changes in instructions can make a different. For example, rather than ‘Write a summary’, change it to ‘Produce a summary’, then discuss what that might mean. Ula’s learners produced a mind map, bullet points, a comic strip, and a paragraph as their summaries, then did some peer feedback before they handed in the work. This is what Ula’s learners thought about these twists to the task:

Some tools Ula and Patricia mentioned:

- www.mindmeister.com – online mindmaps

- www.coggle.it – online diagrams and mindmaps

- www.makebeliefscomix.com – comic strips

- www.voki.com – speaking animal

- www.elsaspeak.com – pronunciation app

Reflecting and evaluating

This could happen after an activity, after a class, or after a specific period of time. It can be individual or in groups. As with all parts of the learner autonomy process, it’s gradual and you need to support students to do this effectively.

- ‘Can do’ statements

- Guided reflection questions

- What did we do today?

- Why are we doing this?

- How will this help your English?

- What makes it difficult?

- How can I make it easier next time?

- Do you prefer to be told what to do or to choose what to do? [Helps learners/teachers to think about goals and strategies for achieving them, as well as encouraging students to take risks and try something new and not just do things which are easy for them]

- 3 things I’ve learnt, 1 thing I’ll do better next week, 2 things I enjoyed

- Reflective diaries (good for helping learners to see how their goals have/haven’t changed over time, what strategies they’ve tried to use, what’s worked and what hasn’t)

- Emoticons work with young learners:

The reflection stage gives you as a teacher useful feedback too about how to improve your implementation of learner autonomy in the classroom.

Tools for reflection online might be:

“Why not just google it?”: dictionary skills in digital times – Julie Moore

This session will explore the unmediated world of online dictionaries, what ELT teachers really ought to know about online reference resources, and how we can pass that information onto our students to point them towards appropriate tools that will prove genuinely useful in their language learning journey.

Julie started off by telling us about the boom in learner dictionaries which happened in the late 1990s and how much the landscape of dictionaries has changed in the interim. Dictionaries are expensive to produce, but sales have plummeted.

Many teachers might still think about dictionary skills in relation to paper dictionaries, even if they use online dictionaries themselves. They also might not think about how to train learners how to use online dictionaries.

Paper v. online

Paper dictionaries are somewhat cumbersome and require some skill to access. HOwever, if learners bought a dictionary they were generally teacher-recommended, reliable and audience-appropriate (designed for learners).

Online lookups are quick, familiar and intuitive. You can use them wherever, whenever you like. You’re not tied to a single dictionary – you can look at lots of different resources. They’re ‘free’ (at least to some extent). However, they’re unmediated and can be difficult for students to navigate. Dictionaries online are for very different audiences and are often inappropriate for learners. They’re sometimes misleading, and it can be demotivating if learners don’t understand.

Dictionary sources

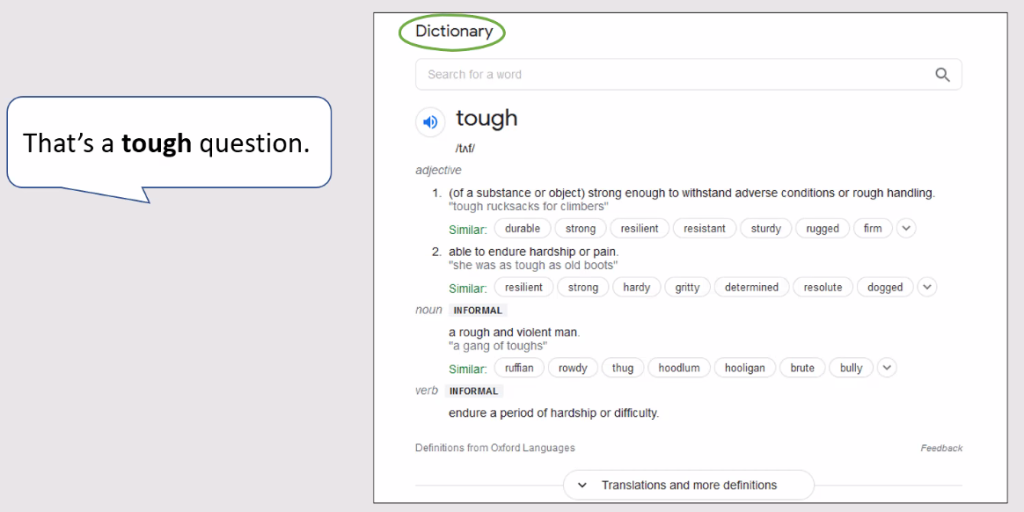

Teach learners to ask: Where is the information from? In the screenshot above, it says ‘Oxford Languages’, but who exactly is that? In this case, it came from Lexico, the Oxford University Press dictionary, and is aimed at first-language English speakers. There are specific Oxford dictionaries for learners though.

Collins Cobuild is aimed somewhere between first language and monolingual learners

Cambridge, Longman and Macmillan also have dictionaries for learners.

Merriam Webster is useful for American English speakers. Their main site is aimed at L1 speakers, but they have a learners dictionary.

The differences between them are mostly about formats – they are all high quality.

How much information is there?

The screenshot above is actually an excerpt from the longer entry. Here is the full entry from Lexico:

Vocabulary in definitions

In L1 dictionaries, the definition is often a higher level than the target word, often abstract and grammatically dense. This is not a problem for most L1 speakers, but can be a real challenge for learners. You can see examples above.

Compare these to learner dictionary definitions:

Learner dictionary definitions generally draw from a set list of words to create definitions, typically a list of 2000-3000 words. This means that B1 learners, maybe even A2 learners, should be able to access the definitions. Definitions are grammatically simple and accessible. Collins Cobuild use full sentence definitions, putting the word into a sentence.

Other information

In learner dictionaries, there is often extra information like word formation, pronunciation audio, Collins has video pronunciation for many words too and a curated set of example sentences. The first example sentence is often a ‘vanilla’ example – how the word is typically used. Many learners won’t read beyond the definition or the first sentence. Further sentences show colligation (grammar patterns), often with with bolded words to highlight the patterns. Sometimes the grammar patterns are spelt out separately, but not always. Other example sentences show collocations.

Learners need to know that all of this is available. Dictionary skills are still vital to teach to help learners work independently.

Teaching dictionary skills

When students ask what a word means, use it as an opportunity to look at a dictionary. In feedback on writing, you can give learners a link to help them find out more about vocabulary – they’re far more likely to follow up than if you just say ‘look it up in a dictionary’. It’s hard to resist clicking on a link!

If lots of learners have had the same problem, bring it into class.

Show learners how to use collocations dictionaries too – the Macmillan Collocations Dictionary is free, the Oxford one is a paid service.

[Unfortunately I had to miss the last few minutes of this very useful talk!]

Some feedback on your feedback – Duncan Foord

Tools and techniques for giving feedback to CELTA trainees and experienced teachers

The workshop is aimed at CELTA tutors and anyone who observes teachers and gives them feedback.

Despite the fact that this activity is probably the key element in the CELTA course and probably the most crucial developmental activity for practicing teachers, CELTA trainers and Directors of Studies are given relatively little training and guidance on how to do it well. In this workshop we will look at effective ways of providing feedback to novice and experienced teachers after observing them teach. Come to this workshop for some tips on how to do it better and how to continue to develop your skills as a trainer and mentor.

Constructive Feedback

- Uses facts in support of observations

- States the impact this had

- Indicates what is preferable

- Discusses the consequences (negative and positive)

Destructive Feedback

- General comments, unsupported with specific examples

- Blames, undermines, belittles, finds fault and diminishes the recipient

- Gives no guidance for future behaviour

- Delivery is emotional, aggressive or insulting

The first area of giving general comments, is probably the most common one that I’ve been guilty of – I’ve worked hard on this part of my feedback.

Thinking about comments

Are these observer comments useful? Is so, why? If not, why not, and how would you improve them?

- You didn’t correct students enough in the lesson today.

- Tell me one thing that went well and one that didn’t go so well.

- Did you achieve your aims today?

- It’s difficult grading your language to a new level.

- Some students arrived late, but that wasn’t your fault.

- Tom (peer trainee), what did you think of Marta’s lesson today?

- Vladimir and Keiko were very quiet in the pair work activity. Why do you think that was?

- Do you think you used ICQs enough?

- How could you set up that conversation task more effectively next time?

This task prompted a lot of discussion in our breakout room. We talked about the usefulness of questions like:

- How did X affect your students?

- How did the students respond to X/when you did X?

- What evidence do you have that X was useful to your students?

These were Duncan’s ideas:

‘Tell me about one thing that went well and one that didn’t go so well’ – this doesn’t give a lot of support in terms of what ‘well’ means, and turns the lesson into some kind of talent show. I’d never thought about this before – definitely going to stop asking that!

Aims – what if the aims weren’t very good in the first place? The changing the aims question invites the teacher to reflect on how useful their aims actually were.

It’s not useful to wallow in the idea of difficulty. It would be better to look at solutions.

We should mention the students in our feedback, rather than focussing only on the dynamic between the tutor and the teachers.

Frame the question from the point of view of its outcomes: Did students understand what they had to do in the role play activity? If trainees can see the consequence, they’re more likely to look for solutions.

Look to the future: How could you…more effectively next time? Rather than How would you have…? What would you have…?

It’s important for teachers to see the consequences on the students, rather than the consequences on the ticklist in yours/the teacher’s head.

Feelings: if the teacher needs to grieve something, or is really upset, you can ask ‘How did you feel about the lesson?’ but if not the question isn’t necessarily that useful.

Key takeaways

- Be specific and mention students all the time.

How well did students understand the language point you were teaching them? How did Vladimir and Lucia deal with that activity? - Work with facts not opinions, the lesson not the teacher.

Abdellah did not participate in the pair activity. - Focus on key points, don’t get distracted with trivia.

What did students learn/practise? Was it useful? What was the atmosphere in class like?

Duncan boils down the essentials of a lesson to:

- Did the students learn or practise anything?

- Was it any use?

- What was the atmosphere like?

This is one way to start feedback. It’s also probably what students are asking about lessons themselves too.

You ask them those questions, and can lead on to ‘What are the consequences of this?’ / ‘What does all this mean?’ It can make it easier during a course for trainees to realise that that’s why a lesson has failed to meet criteria too. If it’s a fail lesson, it can also be easier to tell the trainee right at the start as otherwise they could well be distracted trying to work out if it’s a fail; then the discussion is about what you can do to make it a pass next time.

Coffee break

There were regular one-hour coffee breaks throughout the conference. I went to the final one from the conference. This was a great way to have chats with small groups of people. I chatted to teachers in Toronto, Benin, Moscow, and Saudi Arabia, among others. I really liked this feature 🙂

We were also told about the Oxford TEFL online community for teachers OT Connect, particularly for newly-qualified teachers or for those who don’t get CPD elsewhere, but it could be good for lots of people.

Engaging learners online with hand-drawn graphics – Emily Bryson

Simple drawings are an effective tool to teach vocabulary, make grammar intelligible, and support students to attain essential life skills. This workshop demonstrates innovative graphic facilitation activities to use in class—and will convince you that anyone can draw! Get ready to activate your visual vocabulary to engage your learners online.

Emily stopped drawing as a teenager, but then a graphic facilitator visited her college a few years ago and now she uses it all the time. She trains others in how to use it, and is constantly learning to improve her own drawing.

There is research to show that drawing helps learning to remember vocabulary. There can be a wow factor to drawing too – it’s not as hard as people think.

This is an example of a visual capture sheet:

Emily asked us to use the stamp tool in annotate to mark the wheel to show what we do with drawing already – I like this as a Zoom activity 🙂

Ideas for including drawings in lessons:

- Include images in classroom rules posters.

- Ask students to draw pictures to accompany their vocabulary.

- Introduce sketchnotes.

- Introduce icons which learners can draw regularly, as a kind of visual vocabulary.

- Draw a notebook to show learners exactly how to lay out their notes, especially if you’re trying to teach study skills.

- Use gifs – make sure they’re not too fast as they can trigger epilepsy. You can save a powerpoint as jpgs, then upload it to ezgifmaker. A frame rate of 200 works well.

- Use mind maps. Miro works well online for this.

- Have a set of icons/images – each one could be a new line of a conversation, or the structure of a writing text, or to indicate question words as prompts for past simple questions, like this:

- Create an image to indicate a 5-year plan. Two hills in the background, with a road leading towards them. What would be at the top of the hill for you? What would your road map be?

- Use visual templates (in the classroom or on Jamboard):

- Draw a mountain and a balloon. The students have to work out how to get the balloon over the moutain. The mountain was the challenges facing them in their English learning, the balloon was the learning itself.

- Visual capture sheets can be more engaging:

- Drawing storytelling. Emily uses this to teach phonics as part of ESOL literacy, especially for learners who can’t write in their first language. It gives them something they can study from at home. Emily showed us how she uses a visualiser to help the students see the story as she draws it, with them sounding out the words as they understand the story.

- Use images to check understanding – learners annotate which image is which, or to answer questions.

- Encourage critical thinking, for example by having some images in grey and others in colour.

- Start with a blob or a squiggle. Learners say what it could/might be, and can draw on top of it too:

Anybody can draw 🙂 Emily showed us how to draw based on the alphabet. For example, a lightbulb is a U-shape, with an almost O around it, a zig zag, a swirl, and you can add light if you want to:

For listening, the icon might be a question mark with an extra curl at the bottom, and a smaller one inside, with sound waves too if you want them to be.

For reading, draw a rectangle for the cover, two lines from the top for pages, and some C shapes down the side to make it spiral bound.

For writing, draw a rectangle at an angle, with a triangle at the bottom = pencil. Add a small rectangle at the top, plus a clip = pen. Draw a larger rectangle behind = writing on a piece of paper.

If you’re not sure how to draw an icon, just search for it – ‘motivation icon’, ‘study skills icon’ for example – it can be much easier to copy an icon than to copy a picture. The Noun Project has lots of different ideas too.

As Pranjali Mardhekar Davidson said in the comments, all drawings can be broken down into basic shapes. This makes it much less intimidating!

Emily’s message: Feel the fear, and draw anyway! 🙂 and if you’d like to find out more, you can join one of Emily’s courses. Her blog is www.EmilyBrysonELT.com where there are lots more ideas too. You can share your drawings using #drawingELT

2 thoughts on “Innovate ELT 2021 – day two”